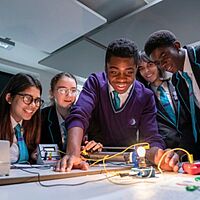

Job creation in the Eurozone has reached a three-and-a-half year high which might present UK graduates with employment opportunities on the continent. Job creation in the Eurozone rose at its fastest level since November 2007, with manufacturing and services enjoying a particular boom in recruitment. Chris Williamson, a chief economist at Markit, commented that many firms in the Eurozone might be taking on new staff to cope with an increased workload.

Whether or not this is a coup for UK graduates is undeterminable. Working on the continent is ideal for only a very specific disciplinary demographic: modern languages student. Others could adapt, by taking short-term language courses aimed at those hoping to work in business abroad, but this is only realistic if their prospective employers will pay for the course. They would also, almost certainly, need to pay for the cost of relocating. This is, all presuming that jobs will go to UK graduates at all: countries in the Eurozone have their own graduates, who would not need to learn the language or relocate abroad. Frankly, it is likely that employers in the Eurozone would only make a commitment to UK graduates if they were struggling to find graduates from their own countries. There would be advantages to working abroad, were a UK graduate to secure a place working in the Eurozone. Despite the initial language barrier, graduates would find themselves eventually in command of a new language, widening the geographical pool in which to search for their next graduate job. Finding a job with a company with a network of global offices would further widen this pool. You could find yourself working in a head office in London, or in Dubai. Economic growth in the Eurozone looks positive; the Markit Flash Eurozone Composite Output Index, which tracks a number of economic growth factors across the continent, rose from 57.6 in March to 57.8 in April. It is important to emphasise that the Eurozone is witnessing the creation of jobs, which is sharp relief against the UK climate in which thousands battle for a single graduate placement.

However, to restate: it seems unlikely that the Eurozone will be a miraculous solution to UK graduates' despair. Eurozone graduates are likely to benefit first; followed by modern languages students; all those for whom the specific employer would have to make minimal commitment for maximum gains. The graduate market is, after all a market, and employers have to make commercial decisions for their enterprise; which in the Eurozone, aren't necessarily skewed towards UK graduates.

Phoebe, GRB Journalist

Whether or not this is a coup for UK graduates is undeterminable. Working on the continent is ideal for only a very specific disciplinary demographic: modern languages student. Others could adapt, by taking short-term language courses aimed at those hoping to work in business abroad, but this is only realistic if their prospective employers will pay for the course. They would also, almost certainly, need to pay for the cost of relocating. This is, all presuming that jobs will go to UK graduates at all: countries in the Eurozone have their own graduates, who would not need to learn the language or relocate abroad. Frankly, it is likely that employers in the Eurozone would only make a commitment to UK graduates if they were struggling to find graduates from their own countries. There would be advantages to working abroad, were a UK graduate to secure a place working in the Eurozone. Despite the initial language barrier, graduates would find themselves eventually in command of a new language, widening the geographical pool in which to search for their next graduate job. Finding a job with a company with a network of global offices would further widen this pool. You could find yourself working in a head office in London, or in Dubai. Economic growth in the Eurozone looks positive; the Markit Flash Eurozone Composite Output Index, which tracks a number of economic growth factors across the continent, rose from 57.6 in March to 57.8 in April. It is important to emphasise that the Eurozone is witnessing the creation of jobs, which is sharp relief against the UK climate in which thousands battle for a single graduate placement.

However, to restate: it seems unlikely that the Eurozone will be a miraculous solution to UK graduates' despair. Eurozone graduates are likely to benefit first; followed by modern languages students; all those for whom the specific employer would have to make minimal commitment for maximum gains. The graduate market is, after all a market, and employers have to make commercial decisions for their enterprise; which in the Eurozone, aren't necessarily skewed towards UK graduates.

Phoebe, GRB Journalist