My time as chief executive of AGR is coming to an end after 15 years in the role. My decision to step down was on the basis that 50 years of full-time work, much of it in high profile professional roles, was enough. With work in my DNA, I aim to build a small portfolio career pursuing interests and causes that I believe in.

Unsurprisingly, as I reach this major milestone I have found myself reflecting on all the changes that have occurred and impacted on the world of work during the past half-century. Technology and globalisation top the list. When I tell my kids that there were no computers when I started work they don't believe me. I can still recall seeing my first computer in 1965. It was so large that my employer had to build an extension to house it - and it only handled the firm's payroll.

Technology paved the way for globalisation of markets. Yes, of course, we imported products from overseas and certain professionals emigrated but that's quite different to the freedom of movement of labour across Europe and the access to markets in every corner of the world for British businesses that exist today.

One less noticeable change, one that has impacted on my personally is the graduate erosion of the statutory retirement age. One of my early jobs was to edit a company newsletter and each month I would attend retirement functions where employees with many years of service, often doing the same job, would receive a splendid gold clock or watch (I never did quite understand the preoccupation with timepieces for people who were going to have less use for them). The retirees would stand up and make short speeches in which they invariably reminisced about their time on the factory floor. It was with immense pride that they would boast about doing the same job, often on the same machine, since they left school at 14, some 51 years earlier.

Imagine a school leaver today being offered a job where they would be trained up to operate a machine for the rest of their working life. Technology and globalisation are not entirely responsible for destroying the notion of a job for life, workers have also rejected that idea. I have mentored young professionals who admitted to losing sleep because they were stuck in a rut after doing the same job for just two years.

Currently in the UK there are 870,000 over 65's in employment, 3% of the total workforce. That's double the proportion in 2001 so it's not just Bruce Forsyth keeping his hand in. There are lots of reasons why older people continue working - financial pressures with the value of retirement annuities falling; better, more healthy lifestyles and a younger 'mentality' being among them.

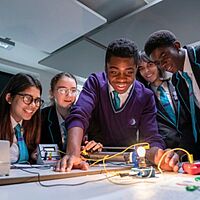

What fascinates me is how businesses handle a wide range of ages within their workforces. From Gen Y, through Gen X to baby boomers and even earlier (what I term war babies) born up to 1946. Add to these groups, Gen Z working their way through school and employers face the prospect of 5, yes 5, generations in the workplace. Managing the inter-relationship between these diverse groups will require increased awareness, understanding and great skill. Of course, the different generations themselves also have to learn how to work alongside and respect others.

This will be one of the great workplace challenges of the next decade and it is not just here in the UK where this is happening - it is occurring across the world. I hold the view that the sooner different generations are exposed to one another and the more time they spend together, the better. Each generation has much to learn from the others. It's a two-way process and not simply a case of older, more experienced generations passing on their knowledge and wisdom. Younger generations have a lot to offer older people too. I find working with younger colleagues stimulating and can work off their energies and ideas. I hope they can tap into my experience, wisdom and knowhow.

In many parts of the world there is a massive and growing problem with youth unemployment. In the UK young people can, on average, expect to be unemployed for 2 years 2 months by the time they are 30 according to the OECD. That's on average. Some people argue that older people working beyond retirement age is affecting job prospects for the young. I don't subscribe to that view but I do recognise the need for government and employers to create many more job opportunities to help new entrants to the labour market kick start their careers.

That's an entirely different challenge and one I will return to in a future column.

Carl Gilleard - Chief Executive - AGR